LORENZO VIGNOLI - sculptor

ARTIST BIO

Lorenzo Vignoli was born in 1981 in the medieval town of Lucca, Tuscany, exposed to art from an early age by parents who nurtured his creative curiosity.

He studied Painting at Central Saint Martin's School of Art in London and Figure Drawing and Urban Landscape at Art Institute of Chicago before embarking on years of formative travels, gathering creative inspirations at artist residences in far flung places like Rwanda, Israel, Bosnia, Ireland and Brazil.

Returning to his home town of Carrara, Italy, he enrolled in the Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara and spent several years working as resident sculptor in the iconic marble emporiums in and around Carrara and Pietrasanta area.

Lorenzo Vignoli's skill of stonemasonry references the classical sense of beauty and aesthetic style of two sculptures in particular, Michelangelo and Rodin. His captivating sculptures are evocative of classical figurative forms as much as they are influenced by modernist abstract movements.

Vignoli’s sculptures have been exhibited throughout Italy and in several public and commissioned projects in California, Australia, China, Brazil, France, Ireland, Israel, Estonia, Rwanda and Bosnia.

ARTIST STATEMENT

After many years of research and study, traveling from country to country, I have realized how much these mountains meant to me. This is the reason I chose the marble from these mountains to manifest my view of life, and express my creativity. Like the roots of a tree, a sculpture is born from the earth. This forces me to look below the surface, beyond the exterior, into the layers of humus and fossils for the inspiration to realize my vision.

I come from Pietrasanta and Carrara, which are historically the two largest centers for sculpture in Italy. Thanks to the sculpting tradition that is deeply settled in my territory, I had the chance to interact with marble, bronze, ceramics plastic, resins and wood, experimenting and exploring the world of materials and the volumes, from ancient tradition to contemporary design.

I tried to grasp the sculpting tradition as a value and its essence through the centuries of transformation by the work of man trying to recover both part of a tradition, which is disappearing, as well as the contemporary elasticity, in its speed and in its ephemeral sensitivity.

My interest lies in examining the encounter of these two aspects as the meeting point of different materials that prompts me to highlight this aspect, emphasizing the point of contact, a sharp line that divides the materials, a line that divides the world of the past from the one of the future like the gap which is growing larger and larger, splitting a unique essence.

The goal of the project is to reflect on this clear separation between the past and the future which is growing vigorously, a clear-cut division between what was before and what is now in our relationship with the physicality of life. My attempt is a positive tolerance, an “atomic tolerance” I call it, between the atoms that make up the different materials, it’s a challenge for the future, it’s not only tolerance among the people but also tolerance towards the matter that people transform.

The project consists in creating and studying the space of division, as in the “gap” between the various materials while creating initially a fractured fusion of the various elements which then are successively sculpted, modeled, ripped apart. I try to experience the maximum separation between the material elements, through linear or forced processes.

My final goal is to structure a dialogue between the various pieces through their own partitions, thus creating the final result of a strong and homogenous effect. I’ve been working now for some time at dividing the elements; I started this project three years ago using materials that I was closely accustomed to such as marble, wood, bronze and ceramics, but I’d like to take advantage of this process to deal with the use of other materials, but faster, experimenting the instinctive gesture of the moment creating an actual installation.

“I was born in one of the valleys of the Apuan Alps, home to the famous white marble quarries of Carrara. Since I was a small child I learned to respect the mountains and absorbed their profound meaning.

My mother instilled in me the sensitivity I have for the beauty of these mountains. My Father taught me to respect them.”

- Lorenzo Vignoli

CLICK BELOW FOR 360 VIEWS OF SELECTED VIGNOLI SCULPTURES

EMBRIONE by Lorenzo Vignoli

hand carved Carrara marble sculpture

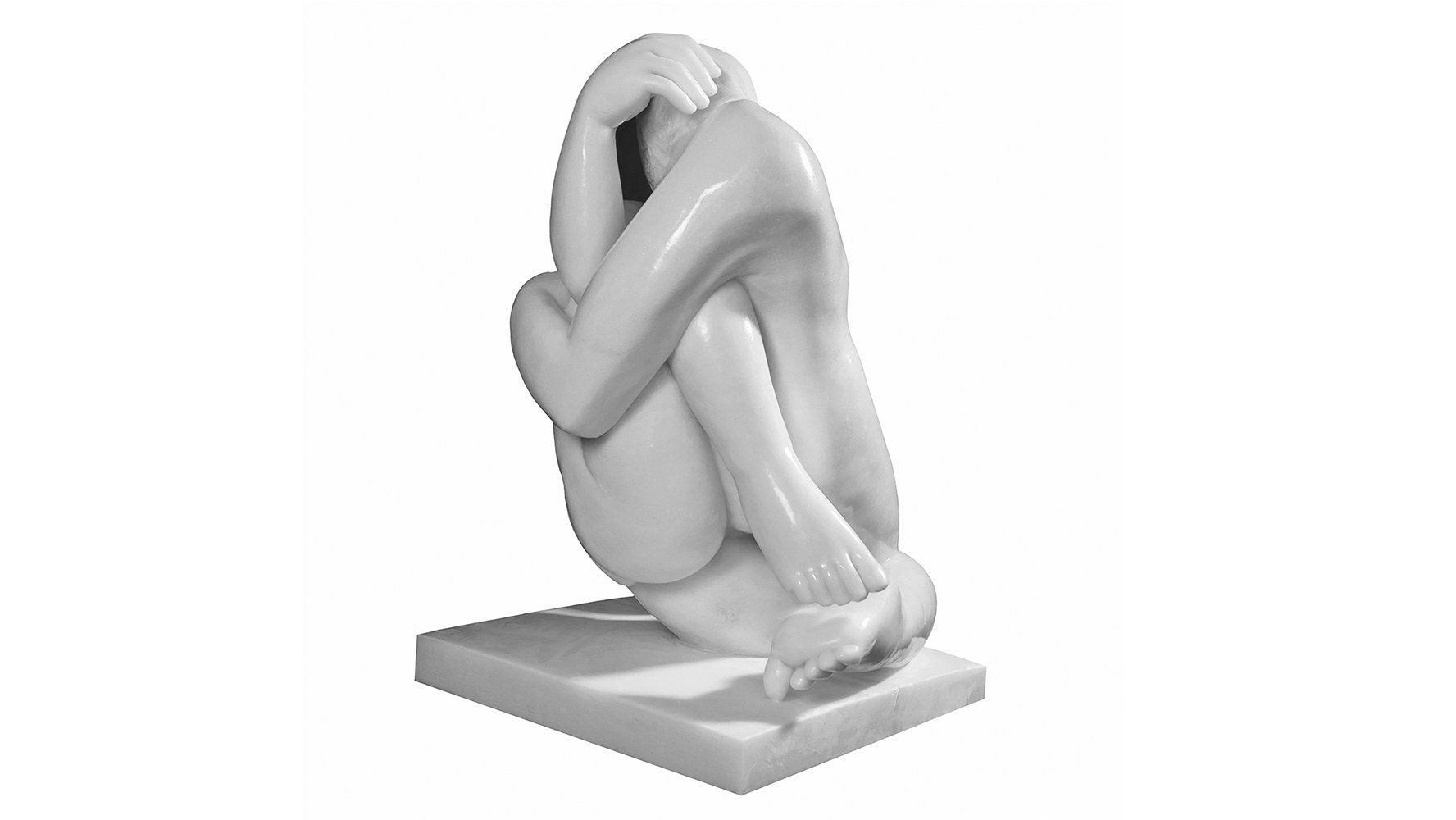

CONTORTIONISTA by Lorenzo Vignoli

hand carved Carrara marble sculpture

MADRE TERRA by Lorenzo Vignoli

hand carved Carrara marble sculpture

BACIO by Lorenzo Vignoli

hand carved pink marble sculpture

UNA VISITA DI STUDIO

A STUDIO VISIT

Vignoli’s studio, immersed in nature in the hills outside of Carrara, enjoys views of Pietrasanta's coastline below and the towering Alpi Apuane mountains in the distance, where the most famous marble in the world is mined to this day …

OBSERVATIONS

Text by Andrea Durio

Translated from Italian

In the season that burns faster than any other, Summer, among the pavilions of the Venice Biennale, before the reinterpretation of Giambologna's the Ratto delle Sabine (Rape of the Sabine Women), conceived by Swiss sculptor Urs Fischer as an immense candle; or perhaps while watching the rotating metal gimmick designed to assemble and remodel wax incessantly, which Anish Kapoor brought to the Rotonda della Besana in Milan, I asked myself if sculpture is not definitively ascribed to the category of disciplines that aspire to be part of a reassuring regime of planned obsolescence. The aesthetic economy of today's world causes a redefinition of beauty that is both cumbersome and uncomfortable. Understood not as a temporary assertion prone like all things, a cupio dissolvi, but rather as the presumption of duration of the residual portion of provocation and of meaning.

Today, even more so than in painting, sculpture appears in latent risk of "irrelevance". Invariably critiques which accompany sculptural exhibitions begin by questioning the possible extinction of this category of expression, and in contrast, the need for a reconfiguration of its semantic boundaries. The result is that the contemporary definition of "sculpture" has come to encompass approaches only distinctly related and seen more in the results than in the process, compared to the traditional definition of the discipline.

It is not known to what extent the paradigm of the "transitional" is helpful in putting back into play the presuppositions of a practice considered in crisis due to the choices made by recognized sculptors - or those whom aspire to recognition - as "sculptors". The use of poor quality materials is often accompanied by technical poverty as well as the choice of a work field which, in best case scenarios, has more to do with handicraft than with the creation of monuments. There is however an instance in which for convenience sake we can call a sculpture “sculpture", or “sculpture squared”. One way of working less "traditionally" - an uncomfortable term associated with a venture into artisan practices and therefore taboo - but more precisely with old techniques applied in relation to matter belonging to our time.

Lorenzo Vignoli, who was born and raised in the Apuan Alps, began as a painter and moved into sculpting after completing his artistic training between Paris and Tuscany. The collaboration with the psychoanalyst Alejandro Trapani motivated him to use sculpture as a way of shedding light on a hidden intro-psychic world. The instinctive choice of marble, a traditional material par excellence, contributed greatly in narrowing the focus of his work. For Vignoli the search for a dialogue and relationship with the material is first and foremost. His is a gradual approach which proceeds by trial and error, by contemplating the misstep, the error, the wrong turn, the restart; as in building a bond that does not have a fore-written ending. There is a modus operandis which is the mere technical translation from the idea to the drawing, and which therefore considers the peculiar nature of each block of marble as an "accident"; a closed deterministic approach, albeit of great technical ability, but which is not Vignoli's. He prefers to wait for the embedded form within the matter to manifest itself naturally, guided by the direct participation of the artist in an emotional event.A sculptor is not a spectator, and the gradual emergence of the work is akin to performance art in which "recognition" and expression are two competing forces. Vignoli's is the synthesis of the school of Canova, which sees sculpture as a three- dimensional extension of the reduced plastic potential of drawing, and that of Michelangelo, which approaches material with a more open mind, with more questions than answers, trying to find images within the marble which mirror our ability to find something in reality that reflects us.

Sculpture is never, except in a derogatory sense, mimesis or an imitation of our world. The amount of naturalism within an artist's production is measured by the awareness that, contrary to the act of painting, a creation ex nihilo, in this case we are dealing with forms trapped inside other forms. One of the characteristics of Vignoli's work is the quest for a type of "ecology of tension” toward the form, which seems to me a type of respect in the face of a too obvious and loud result, a step backward which preserves the triangulation of dialogue and intention between the piece itself, the artist, and the observer who might be able to capitalize on the sculptor's own creative intuitive reserve. But this is not merely an invitation to imaginatively finish the work, or to sand down the unfinished portion with our imagination. There's something different and bigger inside; a feeling of time which has to do with the idea that a specific relationship should not necessarily “end” with a definitive result, but rather as with all things human remain “open”.

Perhaps none of Lorenzo's works respond to the distinctive traits that we tried to outline as in the Contorsionista (Contortionist), in statuary marble, which leads us toward different degrees of completeness, where the torso, head and joints of the figure also combine the real and true formal torment which marks a significant part of the work of this artist. Sculpture's decline toward a simplification of line which belongs to many other fields of expression - invested with questionable artistic gain - is here forcefully denied, and with all due irony, the "Hellenistic and barbaric regurgitation", to which Vignoli has not knowingly renounced, proves that he is not afraid to dissolve the figure in less dramatic formulae.

Dove vado (Where I Go) might seem instead a piece close to the "dissolution of prognosis ". But the apparent withholding of judgment which alludes to the fact that the left arm remains unfinished instead hides a truth that speaks volumes about what sculpture really is: said limb, still in the embryonic stage of the sketch, makes us ponder whether the figure is in fact within the early stages of learning to move. Instead, where the figure is completely revealed as in Se potessi parlare (If I could speak), it would seem brutally obvious that it's the shadow cone which Vignoli still needs to remove, a coincidence between conclusion and closure which is expressed through deformation and through the grotesque, as if perfection belonged solely to the potential world, which later is aborted when it becomes a “precipitate of reality”. We are thus forced to question the "births" of these sculptures, of that which separates and protects them from life and to ask ourselves if the meaning of that incompleteness does not lie precisely in the attempt to nourish the quest for protection against the natural disorder of things.

Birth, mother and nature: among Vignoli's consistently recurring topics, there is one regarding the eternal feminine and -embrace by extension- all that which falls among Gea (the Earth as a Titan) and Genesis, specifically aligned with his fascination with the curved form, translated in a kind of tactile denial of sculptural material, carnal in its sublimation. Where sensorial experience has taught us to use specific perceptual recognition, Vignoli's works Madre Terra (Mother Earth) and Organicità (Organicity) are a type of “suspension" and invitation to abandon oneself to that lyrical material, which is exactly the starting point of every authentic sculptor: a feeling explored by way of circular vision which tries to backwardly and intuitively follow the path employed by the artist. First the approach using tiny steps, the fracture of impenetrability of the marble, then the patient waiting throughout the entire workday, in light grazing cuts which allow terrific bursts of acceleration but which demand however that one is present, “warmed-up and ready” at sunset to intercept the fleeting indication that exposes a possible trajectory hidden until that moment .

The Portuguese pink marble used in Organicità seems to burn beneath the stone's skin where it is still partially imprisoned and signals Vignoli's point of departure in which this exuberance of flesh blossoms without reticence - breaking through the canon held together by muscular plastic - and defining another way of Beauty. In Madre Terra we had thought of creating, in light of the exhibit at Martignana Po, a setting which would give visitors a sense of the space in which the piece was produced; a look into the artist's atelier where the nature of transitional relationships between form and imagination are considered more than the actual result itself, the interwoven discourse between vision and matter.

Alongside these works in marble, we wanted to select examples linked to other materials, starting with the sculpture in olive wood Selvaggia (Savage), one of Vignoli's earliest works - surprising in its ability to transfer and even anticipate its continuous recurring plastic torments - a formal solution which would seem to justify structure, signs, fiber, nodes, fissures and tortuous veins. It is the work in resin however, a precious material which explores linguistic ductility and gestural manipulation of the medium, which complicates Vignoli's work and transcends any prior project. We prefer not to avoid questions of the specific quantity of violence and irresolution insistent in these works, which mark a path at the same time of both advancement and of crisis. Lack of calculation is further proof of Vignoli's position as anti- academic. Overflows, spirals, twists and hypertrophies all allude to the need of attempting to cross inscrutable masses, without turning away from difficult questions into places where sculpture becomes hurtful memory that is not cooled by living flesh.

And it is perhaps by no coincidence that in his most intimate pieces, those dedicated to his mother, Vignoli chose ceramic; it is as though he realized that at the center of this attempt at elaboration there is a melting point, a result which sculpture tries to obtain through pathos but which will tragically occur regardless, albeit externally. But permanent character - that which runs from any programmatic deterioration and the feeling of belonging to a vanishing time - is within the idea that the verb, our small part of eternity, is already inside the flesh: it needs only to be set free.

CAPTURING EPIC SCALE

ON HIGHER ELEVATION

FRANK SCHOTT - photographer

Spending time in the remote Apuan Alps in the spring of 2016, I found myself drawn to the ancient marble quarries on the rugged mountain range's highest elevations, fascinated by the almost brutalist industrial scars that are evidence of the impact of modern day marble demand on mountains and nature.

Most quarries have been in continuous use since Ancient Roman times, although the last 50 years have seen an explosion in demand for the iconic white marble that surpasses all marble "harvesting" of the preceding 2000 years.

Spending days and nights in silent solitude high up in these mountains, hiking solo with a large format camera across high altitude mountain ridges, I came away with an admiration for the scale of these grandiose marble quarries where nature first met man many centuries ago.

I tried to capture their silent beauty void of any sign of life, although on closer inspection each photograph will reveal subtle signs of humanity in the form of a dropped chisel, tire mark or scratched marking - helping to bring the grandness of these quarries into a more imaginable scale.

48 x 72 inches / 122cm x 183cm [ edition of 7 ]

48 x 72 inches / 122cm x 183cm (edition of 7)

68 x 58 inches / 173cm x 147cm (edition of 7)